Summary

On February 21, 2025, a single blockchain transaction updated the on-chain backend of the ByBit cryptocurrency exchange’s Safe{Wallet} multi-signature wallet. The transaction included valid signatures from 3 of 6 signers, presumably all ByBit staff members. Unbeknownst to them, the transaction they had been presented with in the Safe{Wallet} web UI was swapped out by North Korean hackers to give the attackers complete control over the multi-signature (multisig) wallet. Within 13 blocks the attackers had transferred all US$1.46 billion of assets from ByBit’s wallet to the attackers wallet, thus pulling off the largest hack ever in present terms. The attackers went on to launder the assets through a series of on-chain mixers and bridges.

This blog post will provide a comprehensive breakdown of the hack in easy to understand terms. For those already familiar with the inner workings of crypto exchanges, multisig wallets, and hardware wallets, skip down to How the hack happened.

How a typical crypto exchange manages customer assets

Crypto (cryptocurrency) exchanges manage vast amounts of digital assets on behalf of their users. When a user transfers cryptocurrency into a crypto exchange, they typically do so first to a unique deposit address assigned to each user. The crypto exchange will then use an automated software process to sweep the assets from each user’s deposit address into a consolidated hot wallet. User’s assets are commingled in an exchange’s hot wallet, but credited separately in an off-chain ledger, a database. The hot wallet makes it efficient to deal with customer cryptocurrency withdrawal requests, since they can transfer arbitrary amounts of crypto to a user’s wallet in a single blockchain transaction.

(Figure above: Asset flow into and out of a crypto exchange’s hot wallet)

The hot wallet itself consists of a private key that must be secured within the software process that manages the sweeping and withdrawals. If the computer system that manages the hot wallet was ever compromised by attackers, the private key could be used to steal all assets in the hot wallet. The use of hot wallets is a balance of risk and customer experience in terms of being able to respond quickly to withdrawal requests.

When the balances on hot wallets grow large enough, crypto exchanges will transfer the portion exceeding their risk appetite into a cold wallet. Cold wallets are usually also represented by a private key pair, but typically not held online in an automated system. Therefore, transferring assets back out of the cold wallet requires some sort of manual process. For example, a crypto exchange may keep the cold wallet’s private key on a hardware wallet, locked in a safe, and require two senior staff members to be present to connect it to an air-gapped computer to sign a transaction to replenish a hot wallet with cryptocurrency from the cold wallet.

(Figure above: Asset flow between a crypto exchange’s hot and cold wallets)

The ByBit cold wallet that was exploited was not actually represented by a private key, but rather by another type of wallet called an on-chain multisignature (multisig) wallet.

Multisig wallets

In the Ethereum (or Ethereum Virtual Machine, EVM) ecosystem, a multisig wallet is typically implemented as a smart contract that can hold and dispense cryptocurrency according to rules implemented in the computer code of the smart contract. For example, at least M of N (e.g. 2 of 3) signers must approve a transaction to transfer assets from the multisig wallet to another address. A signer is an individual who controls a private key on a hardware or software wallet. The signing threshold is initially set when the multisig wallet smart contract computer code is deployed to the blockchain. The security of an on-chain multisig wallet lies in the fact that an attacker would need to compromise at least the signing threshold (e.g. at least 2 of 3) of signers’ private keys in order to steal assets.

(Figure above: Approval and transfer of assets by signers of a multisig wallet)

One the most popular and widely used multisig wallets is the Safe{Wallet}, by Safe, which spun out of Gnosis. It is an evolution of the earlier, similarly popular, Gnosis Multisig wallet. As an on-chain smart contract, the Safe{Wallet} needs an off-chain user interface (UI) to be able to efficiently interact with this. Safe operates the app.safe.global web UI to do just this. Both the Safe{Wallet} on-chain smart contract and off-chain web UI are open source, which means the source code is publicly available and can be inspected, recompiled, and hosted by anyone.

Hardware wallets as signers

A private key is basically a very long, very random number. It has to be big enough to be and generated randomly enough to be unguessable - think about a number as large as the number of atoms in the known universe. Software wallets (e.g. MetaMask) are computer programs that run on a laptop or desktop computer, or as an app on a mobile device. They generate and store private keys on their host devices. However, as Internet-connected general purpose computers, they are vulnerable to phishing and vulnerability attacks, many of which are specifically targeting cryptocurrency.

Hardware wallets (e.g. Ledger, Trezor) are special-purpose devices that generate and store private keys, receive unsigned transactions, prompt a user to sign these transactions, and then communicate the signed transactions back to the blockchain via a computer or mobile device. They are typically connected to their host device via a simple USB interface, and are hardened against attack.

(Figure above: Ledger hardware wallet connected to a computer via USB)

Both software and hardware wallets need someone to operate them: to review and approve the transactions to sign.

How the hack happened

The attackers were undoubtedly looking at the whole chain of operations of ByBit’s multisig wallets: ByBit staff members with their individual private keys, the off-chain Safe{Wallet} web UI, and the on-chain Safe{Wallet} multisig smart contract.

(Figure above: Architecture of ByBit’s Safe{Wallet} setup)

Rather than attempt to compromise the publicly available source code for the Safe{Wallet} web UI in GitHub, the attackers instead targeted the production Safe{Wallet} web UI deployed on Amazon Web Services (AWS). They determined that a number of Safe staff members had access to Safe’s AWS infrastructure that ran the Safe{Wallet} web UI at app.safe.global. Possibly through a spear-phishing attack, they were able to gain access to one of the Safe staff members laptops and extract their AWS access credentials. From there, they replaced the Safe{Wallet} web UI with their own version.

(Figure above: Attacker phishing Safe{Wallet} employee’s AWS credentials and deploying exploit code to Safe{Wallet} web UI hosted on AWS)

The hacked web UI was almost identical to the legitimate one, except that when a user connected to it and went through the process of initiating a particular multisig transaction, it would display the transaction the user expected to be signing, but in the background it would swap the legitimate transaction out for one of the attacker's choosing.

The Safe{Wallet} on-chain multisig smart contract uses a proxy pattern, which means that it is actually two smart contracts. The implementation smart contract contains the bulk of the computer code, and is deployed once to the blockchain by the Safe{Wallet} team. All future Safe{Wallet} smart contracts are proxies that hold their own state, but rely on the logic of the original implementation smart contract. This allows for upgradeability and a reduced transaction fee to deploy the Safe{Wallet}, at the expense of complexity and broader attack surface.

(Figure above: Attackers replacing the legitimate Safe{Wallet} implementation contract for ByBit’s Safe{Wallet} with one that granted them complete control)

The compromised web UI would only activate for ByBit’s Safe{Wallet}, allowing it to remain undetected until triggered. On February 21, 2025, 3 of 6 ByBit signers approved what they thought was a routine transaction, perhaps transferring assets from the ByBit Safe{Wallet} cold wallet to ByBit’s hot wallet. The attackers, figuring they could only expect to trick ByBit’s signers exactly once, had them sign a transaction that swapped the original Safe{Wallet} implementation contract with one of their own designs.

(Figure: End-to-end view of how the attackers gained control over ByBit’s Safe{Wallet})

The compromised web UI would only activate for ByBit’s Safe{Wallet}, allowing it to remain undetected until triggered. On February 21, 2025, 3 of 6 ByBit signers approved what they thought was a routine transaction, perhaps transferring assets from the ByBit Safe{Wallet} cold wallet to ByBit’s hot wallet. The attackers, figuring they could only expect to trick ByBit’s signers exactly once, had them sign a transaction that swapped the original Safe{Wallet} implementation contract with one of their own designs.

The updated smart contract has two functions which only answer to the attackers: sweepETH, which transfers all ETH from the multisig to an address of the attacker’s choosing, and sweepERC20, which does the same for a given ERC20 token.

(Figure above: Attackers use their control over ByBit’s Safe{Wallet} to steal all of its assets)

It took the attackers only 13 blocks to call sweepETH and sweepERC20 a number of times in succession to complete the theft of US$1.46 billion of cryptocurrency to their own wallet. ByBit had lost all access to their Safe{Wallet}.

Realities of the state of the blockchain user experience

A contributing factor in all of this is that there still remains much to be improved on the blockchain user experience when it comes to signing transactions. The ByBit signers were presumably all using the same Safe{Wallet} web UI at app.safe.global, which was a single point of failure, and not under the direct control of ByBit.

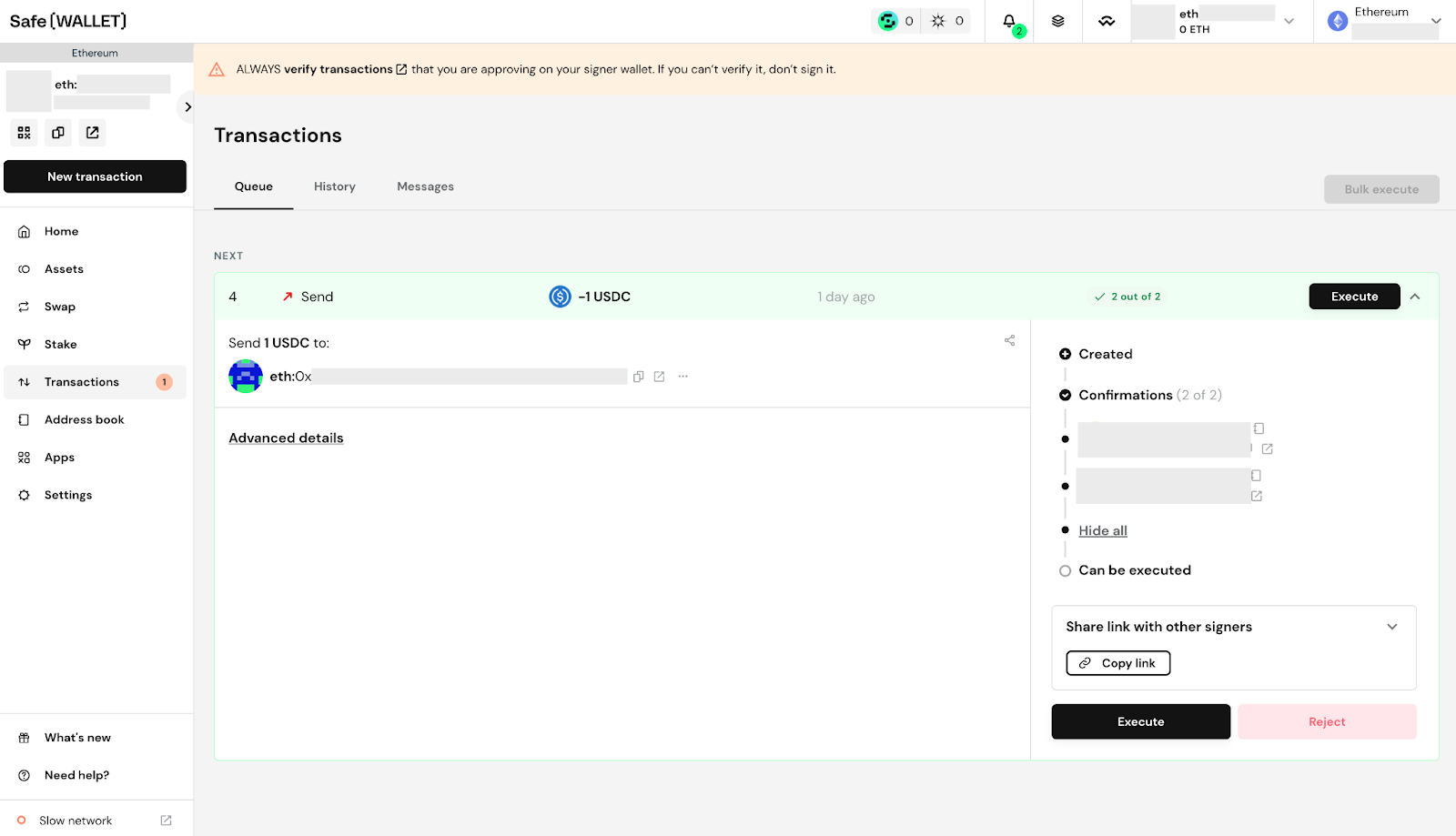

(Figure above: Reviewing a transaction on the Safe{Wallet} web UI at app.safe.global)

From a technical standpoint, a Safe{Wallet} transaction is complex enough that the base models of the Ledger hardware wallet are unable to decode and display key human-readable details about the transaction that is about to be signed.

(Figure above: Reviewing a Safe{Wallet} transaction on a Ledger Nano S Plus hardware wallet connected to a laptop)

Conclusion

Defending against a nation-state actor is incredibly difficult, given their access to effectively infinite resources and an unlimited timeframe. ByBit did many things right, and Safe{Wallet} remains an excellent choice of multisig wallet. However, it’s critical to eliminate or at least mitigate single points of failure in any transaction signing workflow. The Safe{Wallet} web UI at app.safe.global could still be used for transaction approval, but an alternative web UI, like MultiBaas, which supports composing Safe{Wallet} transactions, could be used for transaction initiation. Signers can take the time to check the details and hashes of transactions they are signing. For high value platforms like crypto exchanges, running their own copies of the Safe{Wallet} web UI, with active, round-the-clock information security teams and endpoint protection software, is probably not unwarranted.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the attackers were “testing in production” on Ethereum in the days leading up to the attack itself, via the wallet that funded the gas for the original exploiter’s wallet. They deployed a Safe{Wallet} for testing, and ran through the attack several times, perhaps even via the exploited Safe{Wallet} UI, before springing their trap. The development of better advance monitoring and detection tools can help.

Although a small portion of the stolen cryptocurrency has been recovered, hopefully the industry will learn from this and continue to evolve security best practices along with the wallet user experience.

.png)

.png)